Interview: Camille Valbusa - “Self-Portraits Tell Her Story”

Camille Valbusa is a Brazilian photographer based in California, USA. She has a BA in Journalism and a post-graduation degree in photography from the London College of Communication. She began to photograph in 2011 when studying journalism at PUC-Rio (Brazil) and working for the university newspaper as a photojournalist. In 2015 she moved to London, and after completing the photography program, she started making self-portraits while engaging with critical identity studies and researching artistic practices of healing from trauma. Her work has been exhibited in London, Canada, and the USA.

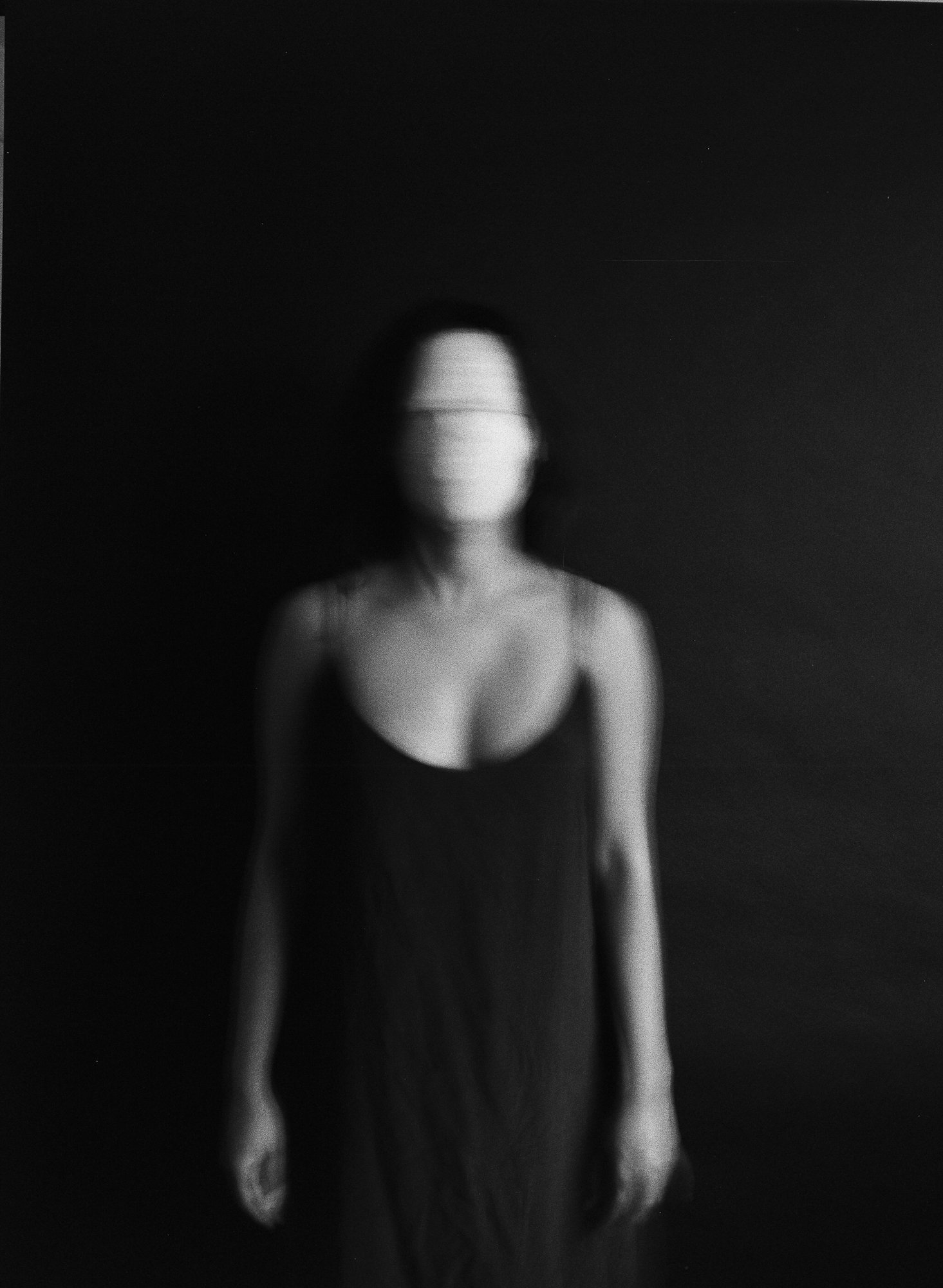

What caught my eye with Camille’s photography was her wonderful self-portraits. Her images tell her story with the use of shadow and movement. They are strikingly dark and ominous but carry a strength and power to them. I appreciate the vulnerability and the narrative quality that is in each photograph. I am thrilled to share our interview where she dives into the motivations of her photography, talks about a current book project, and of course, how shooting film plays into her art-making practice.

INTERVIEW

Rashod Taylor: Tell me little about yourself? What’s your background and how long have you been a photographer?

Camille Valbusa: I am from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I became a photographer almost by accident. When I was studying Journalism for my undergrad degree, I applied for an internship position as a writing reporter at my university’s newspaper back in 2010. I wasn’t accepted for that role, so a friend told me to try to get in as a photographer and then ask to change my position to writer after a couple of months working there. At the time I was interested in photography as a medium but not as a career path. Especially since in Brazil opportunities are not only even scarcer than in other countries but photography is extremely underfunded and disregarded. By then, I had never dedicated myself to it. I selected the best snapshots I had ever taken with my point and shoot camera, and to my surprise I was selected to be a photojournalist. My first month of work was a nightmare because I didn’t know how to use a DSLR camera – I had no clue about composition rules, no editing skills, absolutely no idea about what to do with that camera. Luckily enough, the head of photography at the time was extremely kind and lent me all his photography books and allowed me to borrow the camera from work so I could practice on my free time. After that experience I fell in love with photography as a way of telling stories and to provoke social reflection and, hopefully, change by communicating individual narratives that are always implicated, entangled, with larger social beliefs, practices, and relations. After graduating in Journalism, in Brazil, I moved to London (UK) to study in a one year graduate program in photography at London College of Communication and have dedicated myself to it since then.

RT: What made you get into large format? And why film for your personal work?

CV: When studying at LCC, I was introduced to film photography. I hadn't used film before and didn't know that a large format camera existed. When I had my first studio class, the professor brought us a large format camera for practice, and I was blown away. Looking at the viewfinder under the dark cloth was a magical moment for me. It took me a very long to make my first shot. The process was completely different from what I used to practice. In photojournalism, I was always in a frantic mode, ready to shoot, and with the large format camera, I felt I had time to breathe. After that experience, I slowly started to add film to my practice but never really thought I would move away from digital completely. By the end of the course, I got a job to assist a documentary photographer I really admired at the time. I moved to another country to work with him on a commission for the New York Times Magazine. After working together for a while, the dynamics of our relationship changed, and I didn't feel safe working with him anymore, so I flew back to England. That experience shattered all my dreams of becoming a documentary photographer, which made me get away from the field. Soon after, I began creating self-portraits to help me process that experience, and when I realized it had become my primary practice of photography.

When I began, I had no intention of sharing those images with anyone. However, after a couple of years, I noticed that this process of photographing myself was how my unconscious found to bring deeper wounds, which I had suppressed for a long time, to my awareness. I was communicating something with my body in front of the camera, telling a story through my unconsciousness, saying things I was not prepared to speak through any other media. Shooting film for my personal project made sense at the time. It felt more intimate and less oppressive. When taking those photos, I didn't have any ambition or objectives, so it didn't make sense to look at them right away. I enjoyed being present just with my camera, tuning into my intuition, and not seeing the images in real-time helped me to perform in a free way, disengaged from any expectations or frustrations. It's been six years since I started making self-portraits, and I can't imagine doing them in any other way but with film. I also love the hands-on part of the process and developing and scanning my rolls. It allows me to feel connected to photography in a way that my digital equipment never did and I don't believe can.

RT: I know I have quite a few film cameras and lenses, as I'm sure most of our readers do. However, you typically work with only one focal length at a time. Tell me more about that and how shooting with one focal length has helped your photography?

CV: My main equipment is a Mamyia 645 with a 70mm lens and an Intrepid 4x5 camera with a 210mm lens. In the beginning, I only had one lens for each camera due to financial constraints, and after a while, I came to appreciate that. I feel the less amount of gear I have, the easier it is to know my equipment and get the best out of them. I am aware of the limitations of my lens and also aware of its capabilities. It's very easy for me to visualize how the crop is going to look, and that's extremely helpful in any situation and even more so when taking self-portraits. Shooting with the same lens over and over made my brain memorize and learn the distances I have to be from my camera to have the composition look the way I want. It makes my process easier and faster, with less chance of making avoidable mistakes. When I am scouting for locations to make environmental portraits, it also helps to visualize how my images are going to be and what can be made with the equipment that I have.

RT: How would you describe your style?

CV: I am not sure. This is a very hard question because I've never thought of myself fitting within a style or having a style. I think I am somewhere between documentary and fine art. At some point, I started blending them. It wasn't a conscious choice, but that's the direction that my work moved into. Because my background is in photojournalism, I guess that's always the point of departure when I'm thinking or envisioning my image or projects. As I am creating, I find it easier to navigate through the realms of fine art to convey what I want. I don't believe my images are solely fine art as they are part of a bigger narrative that, at the moment, involves the documentation and the seeking of myself as a woman, as an immigrant, as a victim of sexual abuse, and as an artist.

RT: The work bounces between color and black and white seamlessly. Tell me why you choose to photograph with both? Does one work better than the other for different things?

CV: Yes, they work in distinct ways. Some images can really benefit from the use of color since it's easier to understand the time of the day. It can help suggest the mood I'm trying to set for the photo or bring a nostalgic feeling, for example. Color pallets can be used to evoke different emotions and sensations. I love using color when working with film because it is always a challenge. On Umbra, for example, a red dress is central to the work, and that carries a deep symbolism regarding femininity, the erotic, of a certain risk-taking or a certain danger that it conveys. The dress carries some mystery since red is a strong color that catches our attention, and it guides the viewer through the book. However, some photos don't benefit from the use of color at all. The color doesn't add anything to the image, no information, and it actually becomes a distraction, a noise. Some images are just better in black & white, and they simply don't function otherwise. Black & white can be very powerful to communicate because it is simpler, in a sense, but it doesn't mean it's easier. Sometimes an image only has potency because of the color. Black & white doesn't have it. It needs to be more complex to be engaging, stimulating, interesting visually. I try to use both because I believe that black & white and color are different languages that demand different skills and can complement each other. It is always a matter of trying to understand the "right" moment to use one or the other, and it's a skill that one learns with practice (and, of course, remains somewhat subjective).

RT: I really connect to the work on your Instagram. Do you have any plans to showcase more of the fine art work on your website? How do you balance personal work and commercial work?

CV: Yes, I do. I have been working on updating and making changes to the website, trying to create my own visual brand and find a design that makes sense with the type of photography that I create. I've also been doing a lot of archival work, trying to find past projects that fit with what I've been doing at the moment. It is not a quick or easy process because on Instagram, you are able to showcase single images that stand for themselves but are not really part of a project. Thus, it becomes really difficult to exhibit those single images in a coherent way on a website, that is, in a way that they don't feel lost or thrown together. Instagram seems more like a gallery where you can blend together different bodies of work that have a similar photographic language or visual structure. While they are different projects, nevertheless, they share the same visual language and thus look good together, so it's "easy" to create an interesting page. A website is a bit more complex in that sense. I find it hard to balance commercial and my personal work because their styles are very different from each other. My personal work involves heavier topics and themes that don't necessarily connect or relate to my commercial work. I have recently decided to separate both into different websites. But that's very costly and also time demanding. At some point, I will get there.

RT: I know you have been working on a book project for Umbra. These images seem to be your way to communicate pain and past traumas in your life. It is beautifully done, with something so personal. What gave you the courage to not only make photographs of these things but to work on publishing them?

CV: When I began photographing Umbra, I didn't have the intention of sharing or publishing it. However, many years later, after the project started to come together, I began to understand its meaning and changed my mind. Put together, the photos have a clear narrative that is related to deep social issues. The violence I suffered at different moments in my life is rooted in a patriarchal society that not only allows but also creates space for the violation of women's existence. Not only are our bodies attacked, but also everything related to our existence as a whole. So even though my project emerged from a personal experience, the challenges I was facing and the violence I was struggling to heal from are a common experience to many - if not all - women. We all have had our physical and emotional boundaries invaded at a certain point in our lives, and my main focus in Umbra is not to narrow down on the violence itself but what comes after it. How can I move from a space of pain and detachment and get to the point of reintegration, honoring my wounds, without having those experiences at the center of my identity? To find a way of getting my agency back and understanding that what was done to me is not who I am. What gave me courage is the possibility to share this story with other people and hopefully make them feel held by my story, as other peoples' artwork has helped me in my healing process.

RT: I adore your self-portraits. I want to make sure people understand the challenge of shooting self-portraits with large format. Tell me about your process of making a self-portrait? Do you have help setting this up?

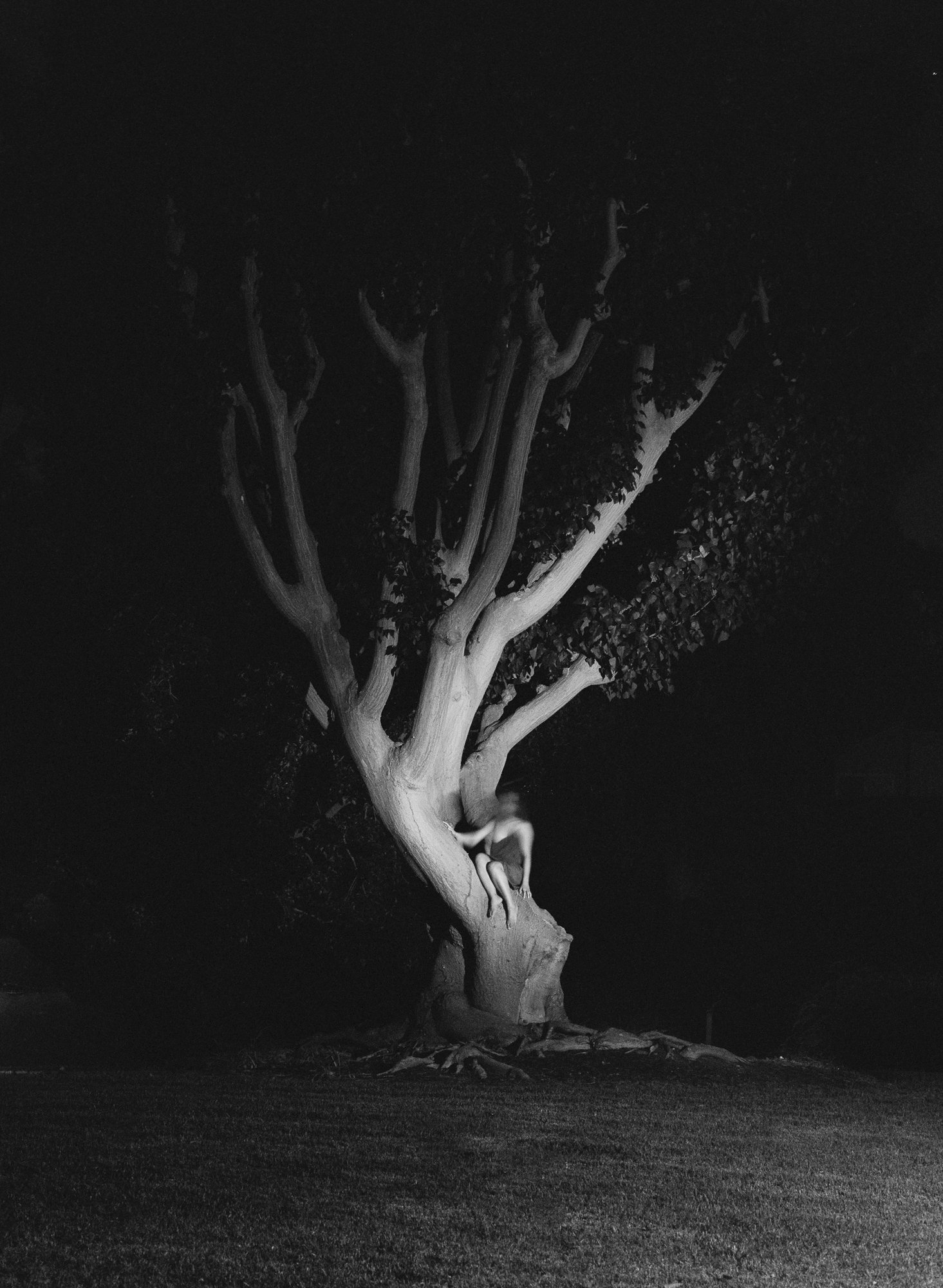

CV: Making self-portraits using a film camera is a challenge indeed. Shooting with a large format is a slow process. I usually shoot a maximum of four photos in a day. It takes me time to load the film, set up the place I'll be shooting, meter the light, and figure out my focus point. Sometimes my husband poses for me so I can adjust the focus, and I generally place a mark on the floor with a tape, so I don't lose track of where I need to stand. However, he is not always at home, so most of the time, I'll use a book and a chair to make the adjustments needed. I also use a blanket whose color is close to my skin tone so I can spot meter the light. That helps since I calculate an average of the exposures for the highlights, mid-tones, and shadows before deciding on the final exposure. I love darker photos, so I tend to underexpose my images and shoot in low-light conditions. Because I only shoot a few frames at a time with the large format camera, I triple-check to make sure everything is correct and always start setting up at least one hour before shooting. My poses aren't planned beforehand. Rather, my aim is to create space for my body to move and flow in front of the camera. It can take me between 10 to 30 minutes in front of the camera until I take one photo. There aren't many attempts to spare, so I try to only press the shutter when it feels that the right moment has arrived. It is a process of connecting with my camera and my body and allowing things to happen at their own time, of guiding myself through my instincts instead of my rational mind. During this process, I don't think too much. I am experiencing a flow of feelings and using my senses to show me the right direction. It is quite hard to explain this process, and it probably sounds a bit weird, but I would compare it to playing an instrument. You have to let your body do it. If you stop to think and rationalize what's happening, the moment will fall out of place. The secret and challenges are to be present.

RT: Your images show a deep vulnerability. I feel like you are bearing your innermost self in these images. What was the process to get to that point with your work? Or have you always been that open?

CV: It has been a journey and has taken a lot of practice. I feel I have always been open to life and experiences, but when it came time to be in front of the camera, things got very intense. Self-portraits became a way of facing myself in a deeper manner, not my physical self, even if it's there too, of course, but more in terms of understanding who I am and how I see myself. Being in front of my camera, even alone feels very vulnerable. I have always felt very much alive and present in my body, and this can, and does, cause a lot of pain, but it makes me fully experience life. Tying back to my photography practice, I started a program in Expressive Arts Therapy, which helped me to be in touch with myself in a way that I wasn't able to before. I learned how to connect to myself intentionally in order to move emotional energy in my body and perform that experience in front of the camera. In my practice, I cross borders of self-judgment. It's as if I am bypassing my superego and allowing my unconscious to flow. In the moment, it is as if I enter a river of feelings and emotions that take over my body, making it move in the direction that it needs to. And that's why using film is so important because I cannot check the results of what I am doing right away. I have to give myself to the process and trust it. Sometimes I have an idea, and that becomes the seed of the image that is going to be created. That's the starting point but not the end. I try to be open to the unknown. That's what I am, at least in a certain sense, trying to capture. When I plan too much, the photos simply don't work. Even though I began this project before studying Expressive Arts Therapy, the course opened the door to new ways of expression.

RT: Your interaction with nature is captivating. Trees, snow, water, etc., how have these things played a part in communicating your story?

CV: Nature makes me feel at home and gives me a sense of belonging. There is no judgment or expectations, no role to be played, or things to do. I can just be myself when I am in that environment, and it really inspires me to create. I experience a flow of energy and a quietness that is very nurturing. Nature is extremely resilient, and it brings us wisdom. Everything is interconnected, there's no separation, and nothing can be rushed. Things take their time, and either they will happen or they won't, depending on each season's context. Nature knows all the cycles of life: birth, pain, scarcity, endurance, growing, plentifulness, decay, death, and rebirth. Observing those changes reminds me that I'm nature as well and that I also have that resilience inside of me. I feel understood and held by its different environments. For example, the snow makes me feel physically what I am feeling internally, so I try to use the surrounding elements to portray my inner shadows. Nature knows hardship, and there's no need to explain anything.

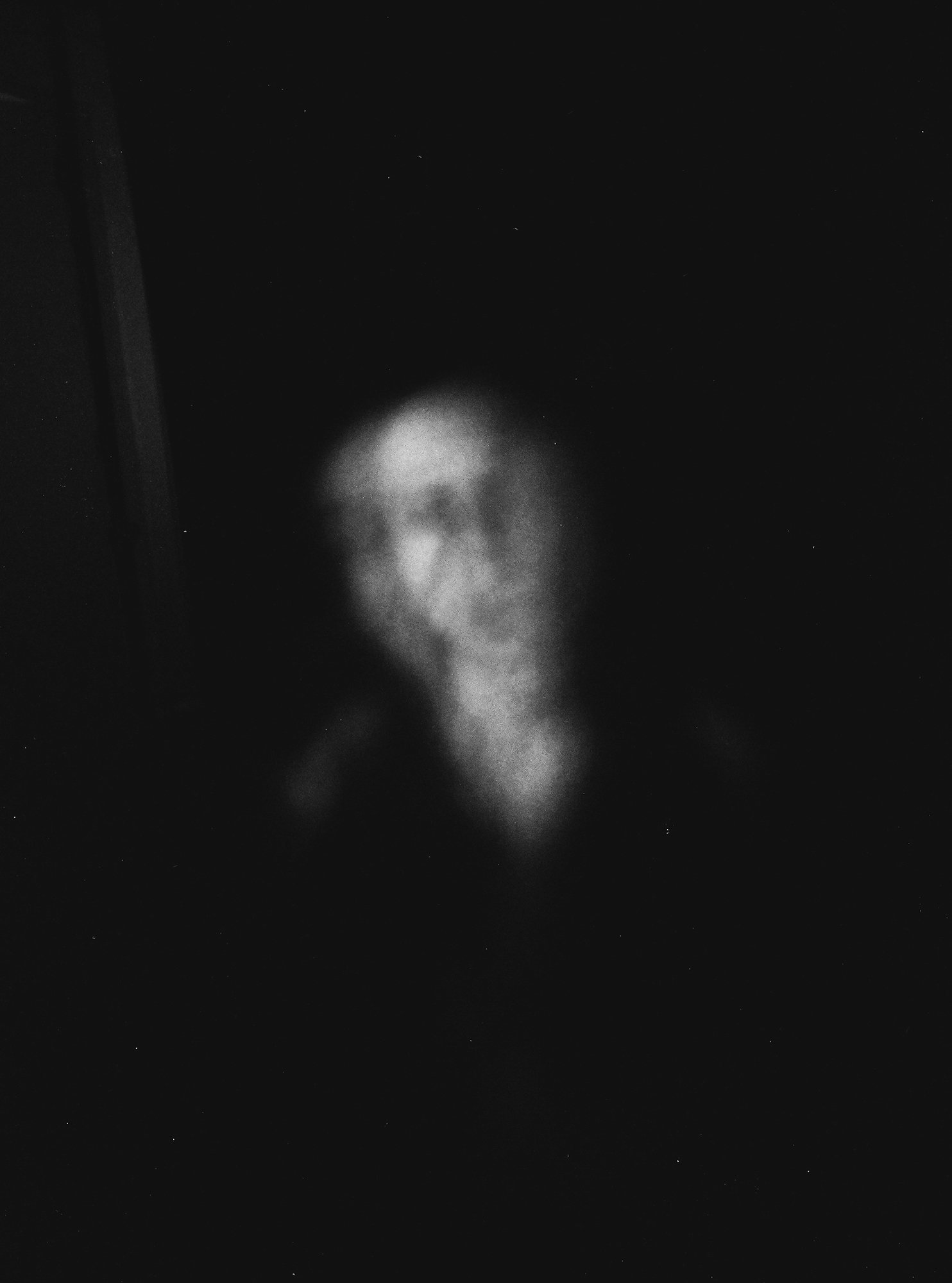

RT: You made a post recently on your IG that brought everything together for me. Your images are so beautiful but at the same time look mysterious and frightening. You talk about having nightmares since you were very young. Can you talk about how that has shaped your work?

CV: My mother's side of the family, whom I grew up close with, has always been very religious. Since I was very young, it was common for me to join the "exorcism" sessions facilitated at the church we went to. As a child, I would get stunned and scared by what would happen in that space. During my childhood, my mom was struggling with different sorts of mental illnesses, including depression and anger control issues, and the pastor would come to our house to free my mom from the spirits that were tormenting her. I don't want to pass some sort of judgment on spiritual beliefs but witnessing those sessions as a child had a tremendous impact on my emotional well-being as I didn't have the tools to understand what was happening around me. Many of my nightmares are from real memories, which makes them even scarier to me. When I think about the past, it is hard to distinguish between what was real and what was a dream. When I began my self-portrait project, I was in a very dark space, struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder, and those spiritual nightmares came very often. On some occasions, I would wake up, and my mind would still be dreaming while my eyes were wide open, so I could see the dream blended with the environment around me. It's a disorder called hypnagogic hallucinations that can be triggered by stress. Photographing the mysterious happens very easily for me because, at many times, I have struggled to draw the line between the real and the imaginary worlds.

RT: Your work is wonderful, and you are super talented. So what's next for you? Are you working towards anything in particular?

CV: Thank you so much for such kind words. At the moment, I am finishing editing Umbra in the form of a photo book and researching ways to publish it. There's much more work involved than I thought before I began this process. I am also starting to work on a new project, which is, in a way, a continuation of Umbra, but it is not a "sequel." I am not at the same place that I was when I started working on Umbra; thus, the project has become something else. There is a moment when projects shift; I believe they are always related, there's no total rupture, but they also stand on their own. Recently I went through family losses, and they were my first experiences with the death of people that were very close to me. Since they've passed, I've been documenting the grieving process of losing someone in the middle of a pandemic, far away from my home city, not being able to be a part of the rituals of passage with my family, and having to grieve on my own, isolated from my community. I will continue dedicating myself to researching the relationship between photography and trauma and how art can be used as a tool of transformation.

GALLERY

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Camille Valbusa (b. 1992) is a Brazilian photographer based in California, USA. She has a BA in Journalism and a post-graduation degree in photography from London College of Communication. She began to photograph in 2011, when studying journalism at PUC-Rio (Brazil) and working for the university newspaper as a photojournalist. In 2015 she moved to London and after completing the photography program she started making self-portraits while engaging with critical identity studies and researching artistic practices of healing from trauma. Her work has been exhibited in London, Canada and the USA.

Connect with Camille Valbusa on her Website and on Instagram!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rashod Taylor is a fine art and portrait photographer whose work addresses themes of family, culture, legacy, and the black experience. He attended Murray State University and received a Bachelor's degree in Art with a specialization in Fine Art Photography. Since then, Rashod has exhibited and published his work across the United States and internationally. His work is currently on exhibit in the group show, Reflecting Voices at the Colorado Photographic Arts Center in Denver, CO. He is a 2020 Critical Mass Top 50 Finalist, winner of Lens Culture’s Critics Choice award, and a 2021 Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards winner. Rashod’s clients include National Geographic, The Atlantic, Buzzfeed News, and Essence Magazine. He is currently working on a series called Little Black Boy, where he documents his son’s life while examining the Black American experience and fatherhood. He lives in Bloomington, IL, with his wife and son.

Connect with Rashod Taylor on his Website and on Instagram!

Camille Valbusa’s self-portraits are critical identity studies that research artistic practices of healing from trauma. Read our latest interview where she dives into the motivations of her photography, talks about a current book project, and how shooting film plays into her art-making practice.