Interview: Patricia Bender's Photograms - Euclidean Pursuits

Photographer Patricia Bender is a Midwestern transplant based in New Jersey. Initially a dancer by calling, for the first decades of her life she performed and choreographed, and even taught David Bowie how to tap dance. Since retiring from that life she has committed herself to photography, focusing on traditional black and white darkroom work. She has most recently been recognized with the 2018 Critical Mass Top 50, publication in Harpers Magazine, inclusion in the permanent collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and a November 2018 solo show at Frames and Framers in Short Hills, NJ. In February 2019 she will have a solo exhibition, Euclidian Pursuits, at the Hampshire College Art Gallery in Amherst, MA.

I'm not sure when or where I first came across Patricia Bender's striking photograms, I only know that at some point I clicked “Follow” on Instagram and was always compelled to hit the heart whenever one of her graphic compositions appeared in my feed. These days we are constantly inundated with images, our brains are assaulted by content from the minute we wake up, but sometimes an image will break through the noise and make us pause and reflect. But what is it about Bender's photograms that consistently captures my attention?

In an attempt to figure out this mystery, I spoke to Bender from her home in New Jersey. We soon bonded over our shared backgrounds rooted in physical art forms and pondered how these early practices might influence how we channel the artistic impulse into other forms of expression. How do our experiences of the world shape our artistic tendencies? What is the nature of abstraction, and why does it have the capacity to move us deeply? We chatted about these questions and more.

For those who are unfamiliar, photograms are created by using traditional darkroom paper and instead of using a negative objects are placed directly onto the paper and then exposed to light to create one of a kind images. Bender uses drawings and cutouts to create her graphic compositions which she prints onto silver gelatin paper.

Connect with Patricia Bender on her Website and on Instagram!

Interview

Niniane Kelley: I really don’t know very much about you, honestly. I don’t know how, but somehow I started following you on Instagram, and your page is very much focused on your work, so it’s just like, I don’t know much about who you are, I just know these images.

Patricia Bender: I’ve been working away very quietly on my own for about 15, 16 years now. I can always remember when I started photography, it was 9/11. I went to take my first photography class and the tragedy happened and it was cancelled, so that was when I first started studying photography. So it’s been about 17 years, which is hard to believe. But I’ve been just plugging away doing my thing, mostly in New Jersey and Michigan, which is where I’m from originally. And just recently with this body of work it’s really caught on and gotten some attention, so more people know who I am now, which is strange!

I’m a late adopter on just about everything. I do analog only, from the beginning I’ve just used analog cameras. I’ve never had any camera that does anything for me, I really don’t know anything about digital, and I’ve always worked in the darkroom. So, I’m kind of late to social media. I didn’t do Facebook for a long time and I just started Instagram, I don’t think I’ve been even doing it for a year. So, all of that’s kind of new for me as well. And it’s been amazing, especially Instagram. I like the visual nature of it, and I think that’s led to a lot of people seeing my work who have never seen it before.

NK: Tell me a little bit about your history and your background, you said you grew up in Michigan and now you live in New Jersey.

PB: I’m a midwesterner; I was born in Iowa and moved to Michigan in third grade and went all the way though high school and a couple years of college in Michigan. I got married and my husband’s job brought us to the East Coast, so I ended up finishing up my college degree at Rutgers and we’ve been on the east coast ever since. And my initial love was dance, that’s what I did for the first 25 to 30 years of my life. It was my passion. I performed and taught in New Jersey and Manhattan and when I decided I wasn’t going to perform any more and I didn’t want to choreograph or teach I kind of floundered around for quite a few years trying new things, a hodgepodge of things. I wouldn’t even call them careers, they were just things that I experimented with. And when I found photography I was shocked I found something that I really loved as much as dance, and I’ve been really passionate about it since then.

NK: Yeah, that really interested me when I read it in one of your artist statements, because I actually have a similar background in that I was a figure skater. I have the same experience in being involved in movement and choreography and then having that go away and needing to fill that artistic void, and that’s how I ended up getting into photography.

PB: That’s interesting! Because it is, it’s all consuming. And because people don’t understand with dance, and I’ve often compared it to sports, but you’re still young and in the thing that you love to do the most you’re considered old! And it’s a very strange feeling to be in your twenties and be told that you’re too old to do this kind of stuff any more, and all of a sudden what are you going to do? Basically, you can teach or you can find something new, and to find something new is hard to do. But I was thrilled when I found photography, I really was. I tried writing a lot, worked as a journalist for a while and did a lot of personal writing with poetry and journals, but I like the freedom of photography, the visual nature of it. When you’re writing you’re so in your brain and I like the freedom of getting out of my mind, and I feel that photography really does that for me.

NK: In your earlier work you got really into working in abstraction, even though you were still taking straight black and white photographs.

PB: In my early work I really loved nature, I loved to be out in the world and exploring, especially the natural environment. I’m kind of a loner and I like to be out alone in the woods or near water, and even when I’m shooting in a city I’m always looking for abstract scenes in the world. What I feel is my first really successful photograph was in New Orleans and it was this billboard where people would staple up announcements and then rip them off and staple over them, so it was this really cool almost Siskind-y abstract of staples and torn paper and parts of words. And I would do that kind of thing in nature as well. And from the beginning I’ve always worked in black and white, I’ve never worked in color at all. I like really tiny pictures, so I’ve always worked very small, 8x10 is really big for me. I’ve also experimented a lot with multiple image pieces, I like doing that, too, creating narratives with several small images together. I always want to pull the viewer closer to my work, I want them to have an intimate experience with it.

NK: With your early work, you said that you were very influenced by Callahan and Siskind, following in their model of creating graphic abstractions of reality, and I can see that in those images. How do you think that has informed this new cameraless work that you’re doing?

PB: Oh, wow, that’s a hard question. I don’t see how the cameraless stuff evolved, really. I think I needed a break from film and I was trying a lot of different stuff, and I’ve always liked abstract work. A lot of the images now are hand drawn paper negatives that I use, and I had never drawn before, either, so I think part of the appeal of what I’m doing now is the newness of the drawing and seeing where that takes me and trying to translate that into a photographic image. Abstraction has always been a form of art that I’ve loved, I think primarily just because it moves me so strongly and I don’t understand why. I’ll look at a Cy Twombly painting and go, “Why does that sway me?” And I think that it’s the mystery of what it is that’s moving me so much, and that makes me want to try to draw that and create that myself.

NK: That’s actually one of the things that I’ve been thinking about looking over your work the last couple days, why do I like these? What’s drawing me to these lines and forms that don’t necessarily say anything in themselves, but they’re obviously saying something to me!

PB: I was trying to do a bit of research and thinking about it and I was wondering if there are, like, primal forms in our memory that abstracts are activating. I read that a triangular face is typically a predator, so maybe triangles for some reason…

NK: Are more threatening?

BP: Yeah. Maybe certain forms, certain shapes, certain patterns together speak to us, to some reference in our mind that we aren’t even aware of. And I mentioned earlier that I write a lot, and, for me, visual art shouldn’t be about words. If I wanted to express an idea to you, I would write it, if I wanted to move you, for me it’s visual. It’s a way of bypassing words, bypassing the brain, and going straight for the emotions, and that’s what visual art does for me. So when I create work, I don’t necessarily have a message.

NK: Or maybe you don’t even know what it is!

PB: (laughs) Yeah, that’s exactly right!

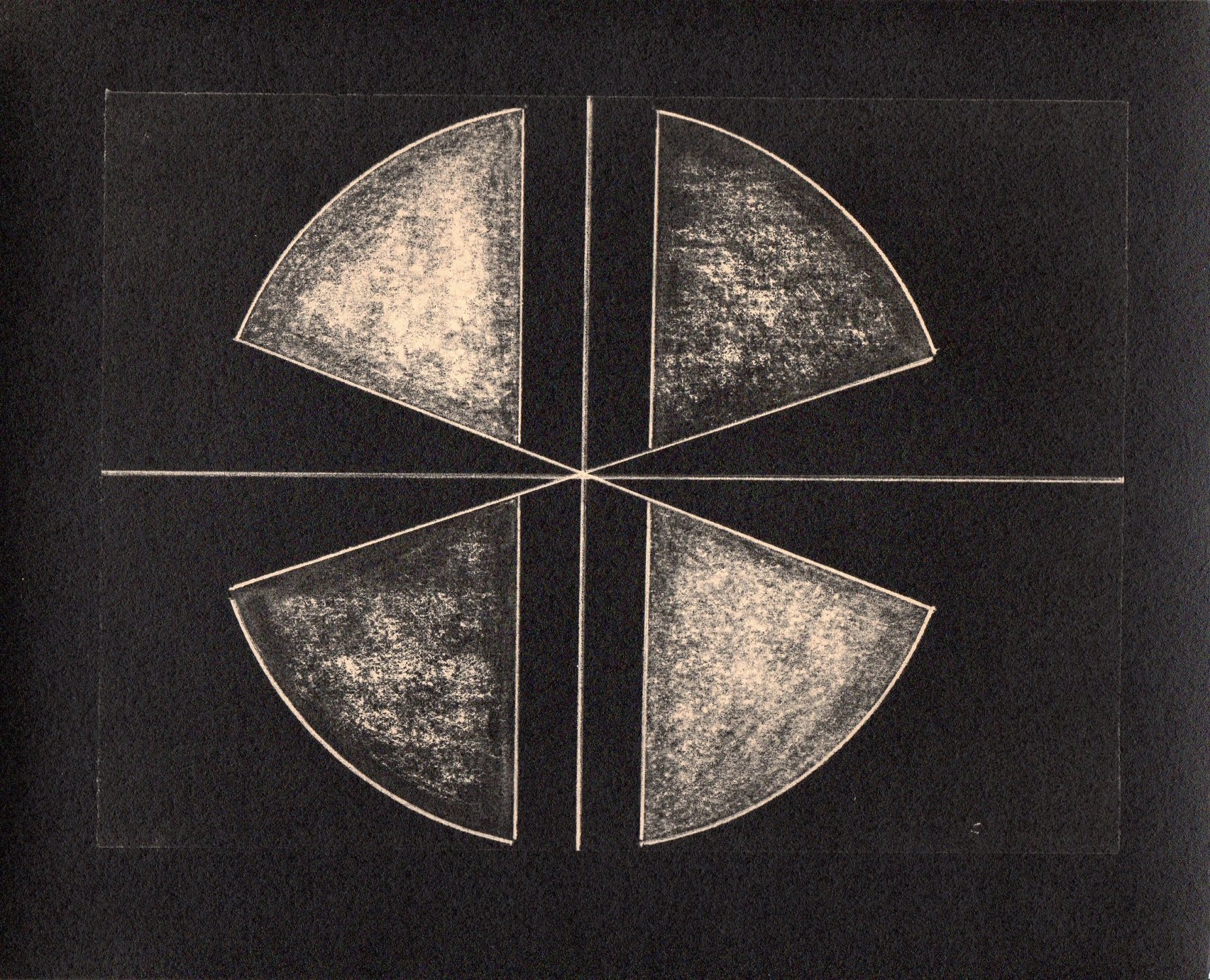

NK: So looking at these pieces now I’m seeing them in a couple different ways. One is a connection to your past as a dancer, because dance is an abstract representation of a concept or an emotion. You’re making shapes and patterns in space, and it’s how those shapes and patterns interact. Looking at some of these pieces I can see how they can be the basis of a choreographic form. I’ll look at, say, this one that looks like a sunburst and see how that could be translated to physical movement.

PB: Yeah, that’s true. I’ve never thought of that, that’s a really good point. I’ll have to think about that, I love that thought. There is a sense of motion and movement in them that I’m seeing when I’m creating them as well, and I think that comes through.

NK: You’ve talking in one of your statements about particular Georgia O’Keefe and Lee Ufan paintings that you love that have these very simple shapes, and I’m looking at these pieces now, and it’s really the gesture of the shape that’s captivating. And then you can also imagine the movements that are required to make those gestures on the canvas; it becomes more than just a brushstroke, it’s an experience of a brushstroke. There’s a sense of movement and presence, a physical representation of this ephemeral moment for the artist.

PB: Yes. And when I’m doing it it’s very intuitive, it’s really a flowing thing, which is what dance is, also. When I create them I don’t pre-think them, I just start and see where it goes. And sometimes when it works, like with dance, it is wonderful, and sometimes it doesn’t work and you just start again.

NK: And another thing, which you’ve alluded to, is that this work is also dealing with geometry and mathematics, and mathematics is its own form of non-verbal communication; it’s the basis of everything we understand about the universe, it’s the underlying structure of everything. And looking at the images as a whole, it’s almost as if the images are trying to convey something in their form, like there’s a language in them that we’re trying to decipher, but what is this cryptic language saying?

PB: Yep. And my hope is that is says something different to everyone. Like I said, it’s not me trying to say something to you that I’m trying to convey visually, but I hope it says something that you will discover yourself, that it moves you. If it moves you and makes you wonder why, and that makes you examine it even more, that’s a wonderful thing.

NK: And some of them look like a scientific drawing you’d see in a textbook on physics or astronomy or math, so it seems like there’s some underlying scientific nature to all of this.

PB: I just did one today that I loved, and I looked at it trying to figure out why, and it reminded me of molecules. So then I googled molecular structures, and all of a sudden I discover all these technical diagrams of molecules and there’s this whole discipline called molecular geometry that I have to start learning more about. So it may be that the knowledge of these scientific forms is just innately in us somehow and it’s there to come out.

NK: Yeah, exactly. From the time we had any sort of consciousness we were tracking the movements of the stars and the sun, and creating this idea of sacred geometry because we knew that there was something important in the interaction of all these elements around us. From the beginning we were trying to understand our world through these forms.

PB: It’s so true. And that’s the thing that’s exciting for me, because I don’t have an art background this has opened up a whole new world for me. I’ve been doing a bunch of research on abstract artists I’ve never heard of before, and then to start studying, like you said, the sacred geometry. Just today I was looking at the Native American patterns and forms that they’d use on their pottery and their clothes and fabrics and it’s just fascinating. The thing that’s daunting is that it’s just so huge you could spend the rest of your life studying this idea. I find it wonderful, I really enjoy it a lot, I love learning.

For instance, I recently got this comment that they felt I should acknowledge the artists who influenced my work and they started listing all the Bauhaus artists, and I didn’t even know it because I don’t have an art history background. So I went back and was looking at Moholy Nagy, and, that’s right, his work really does look a lot like the kind of stuff I’m doing! And I’m sure I’ve seen it in the past, but it’s interesting how an artist or an art movement can influence you without you even knowing it, and this person was angry at me because I hadn’t acknowledged it. But it’s been interesting, people with art history backgrounds have all pointed out different people who my work reminds them of, too, which has been an interesting thing to learn.

NK: And it’s hard to say what is just osmosis from maybe seeing it in a museum for half a second and how much is that this is just how the human brain works. It’s what we’re all seeking and looking for and sometimes people stumble upon the same concept over and over, and that itself is really interesting.

PB: It is. And there’s obviously something there because these forms still speak to people today that spoke to people hundreds of thousands of years ago. There’s something in our minds that they’re touching and it’s interesting to explore and try to figure out what it is.

NK: So tell me a little bit about your process, how do you go about making your images?

PB: What I’m doing right now, I spend a couple days drawing, mostly with graphite, and I’ve been experimenting with layering it, smudging it, burnishing the drawing itself. I love to experiment, so I’m always trying new things. And I’ll do cutouts with different kinds of paper and layer them. Then I’ll take it into the darkroom and contact print it on fiber paper.

I like experimenting with different papers. I collect old expired paper, and people will give me their old paper because they have stopped working in the darkroom.. A friend of mine introduced me to this concept call oxidizing, where you expose the print to natural light between the stop and the fix, and when you do that you can get different tones in the highlights, so I experiment with that as well.

That’s another thing about photography and art, there’s so many things that I want to do, and there’s not enough time in the day! I’ve started experimenting with sewing and using thread, and I like that a lot, and I’d like to get back to doing that. And I also started drawing on the final print, the images where there is color are ones I’ve drawn onto the print. I tend to get bored doing too many of the same things, so I’ll try something new and then sometimes go back to things I’ve done before.

NK: One thing about a lot of your images, from using the paper negatives and pencils and crayons, they do have texture to them which gives them some extra depth. They’re not that strict black and white, positive/negative that one generally gets with photograms.

PB: Exactly, and I’ve loved playing with that a lot, using the graphite and doing rubbings with bark or rocks within the forms to play with texture. I experiment with that a lot to give it, like you say, a depth in the image as well, so it’s not quite so flat.

NK: You’ve been focused to these photograms for the past year or so, have you put the camera away entirely for now?

PB: I still shoot, but not nearly as much as I did. And it’s unfortunate because I just got an 8x10 and I was really excited about that, but I haven’t taken it out in a long time. I think I needed a break from shooting so much, but I will get back to it. I can’t ever imagine giving up film. But also, then the whole way the world is right now, it made it hard to focus they way I need to with a camera, whereas this photogram work is better at taking me out of my head and letting me leave this world behind for a little while. So this kind of work is therapeutic for me.

NK: And there is something therapeutic about disappearing into the darkroom for six hours at a time!

P: Exactly! That’s for sure!

Gallery

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Niniane Kelley is a fine art photographer living and working in San Francisco and Lake County, California. A native of the Bay Area, she is a San Jose State University graduate, earning a BFA in Photography in 2008. She teaches workshops in the Bay Area and surrounding environs. She most recently worked as a photographer and manager at San Francisco’s tintype portrait studio, Photobooth. Connect with Niniane Kelley on her Website and on Instagram!