Book Review: “O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South”

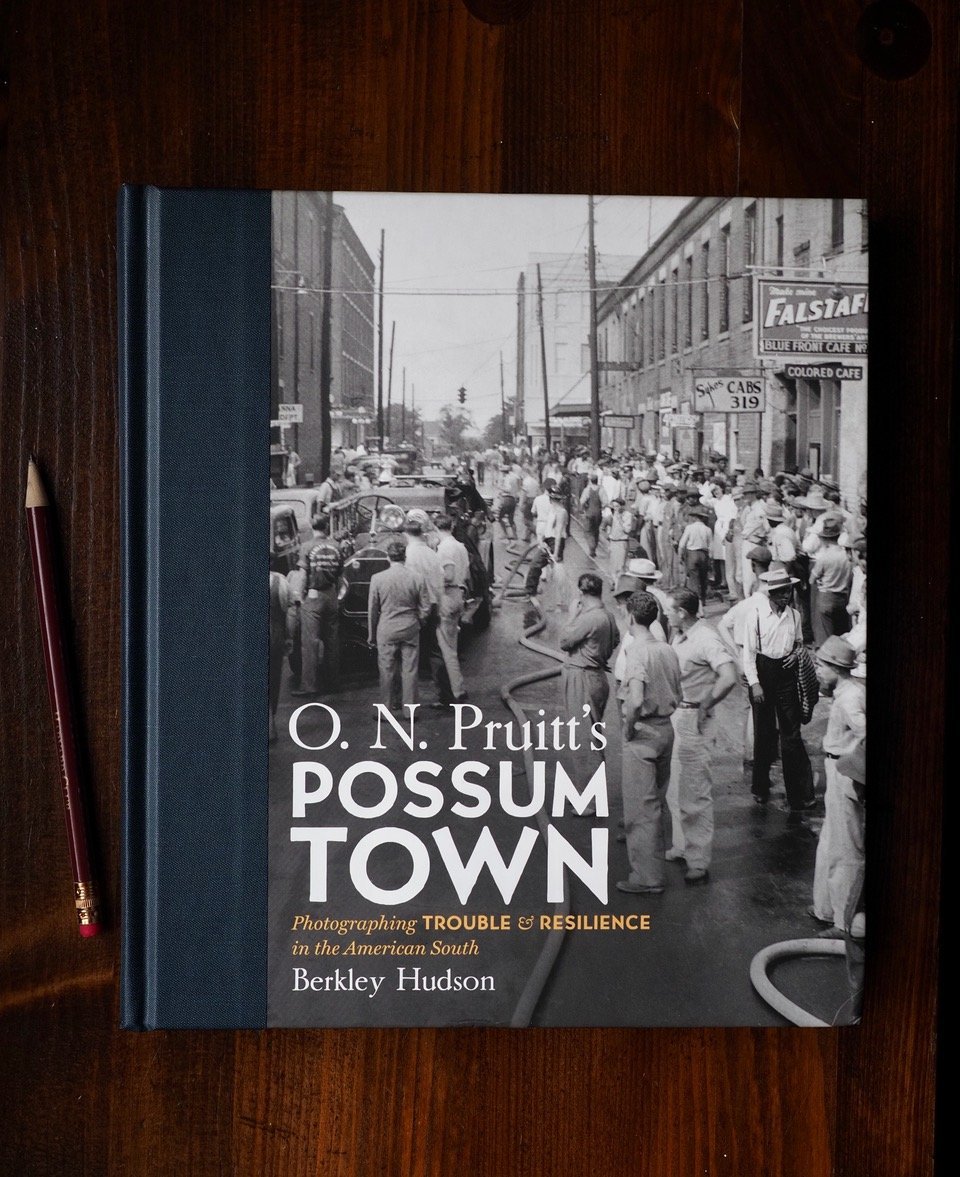

O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South, by Berkley Hudson, rescues the photographic legacy of O.N. Pruitt (1891-1967), and brings to life early to mid-20th century Columbus, Mississippi, known to locals as “Possum Town,” where Pruitt worked for 40 years as the de facto chronicler of both everyday life and special occasions. The book contains 194 of Pruitt’s photos, and essays and explanatory text by Berkley Hudson, a Columbus native whose family was photographed by Pruitt. One of the family photos includes Hudson as a baby. The book is an homage to Pruitt himself, a testament to the persons and places pictured, and a product of the foresight of Hudson and several friends in pursuing the idea of purchasing and preserving the archive.

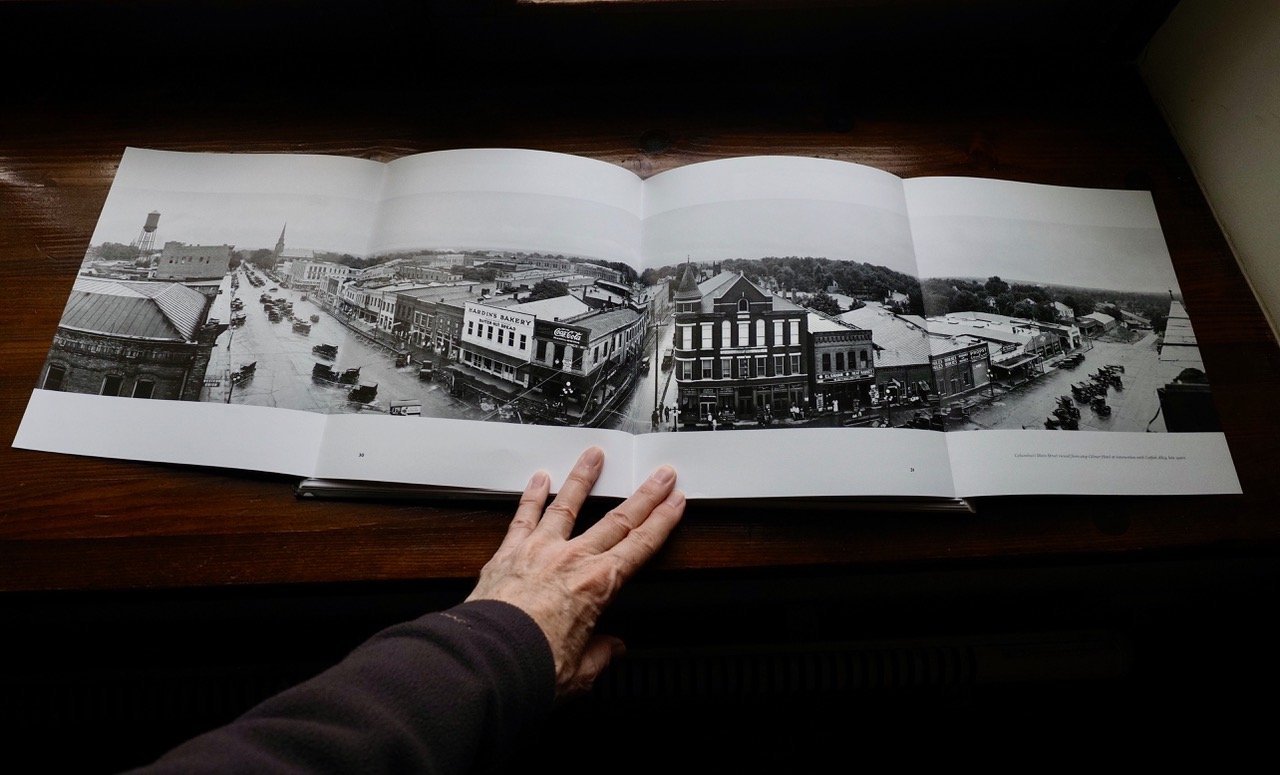

Pruitt retired in 1960 and the archive was retained by the photographer who took over his studio. Upon seeing the archive some years later, the idea of preserving it took hold of Hudson and his friends, and they were eventually able to buy it—some 88,000 Pruitt images on smelly nitrate and acetate negatives and glass plates up to 8 x 10 inches. But having determined they should be saved, what exactly were they going to do with them? Decades passed with many twists and turns before this book appeared, during which Hudson went on to work as a newspaperman, and then to teach at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. Hudson turned the collection into a research project at the University of North Carolina, and the photos were finally placed in the Southern Historical Collection of UNC library. The book is a relatively compact 9 x 10 inches, but its 272 pages weigh in at over 3 pounds, printed on very heavy paper.

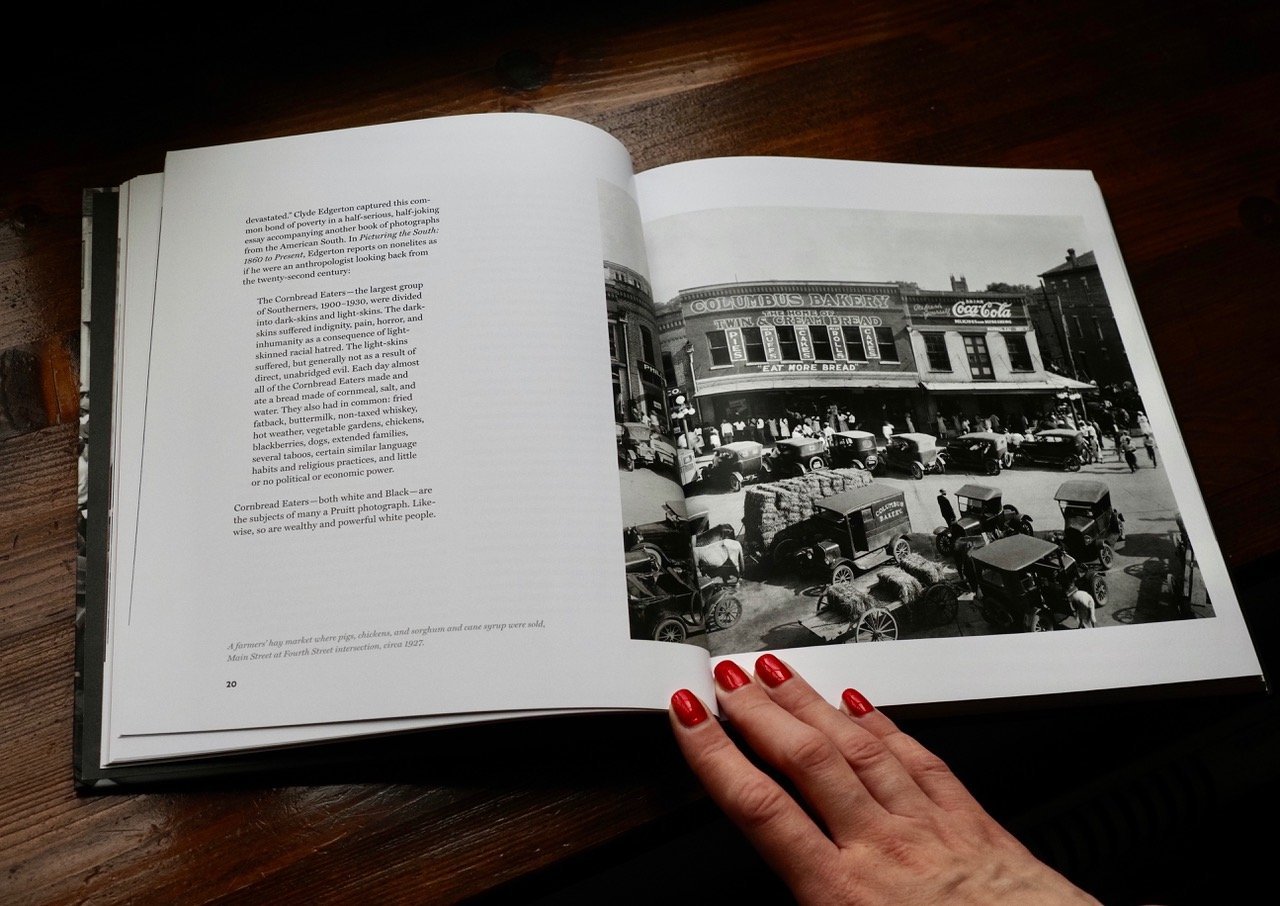

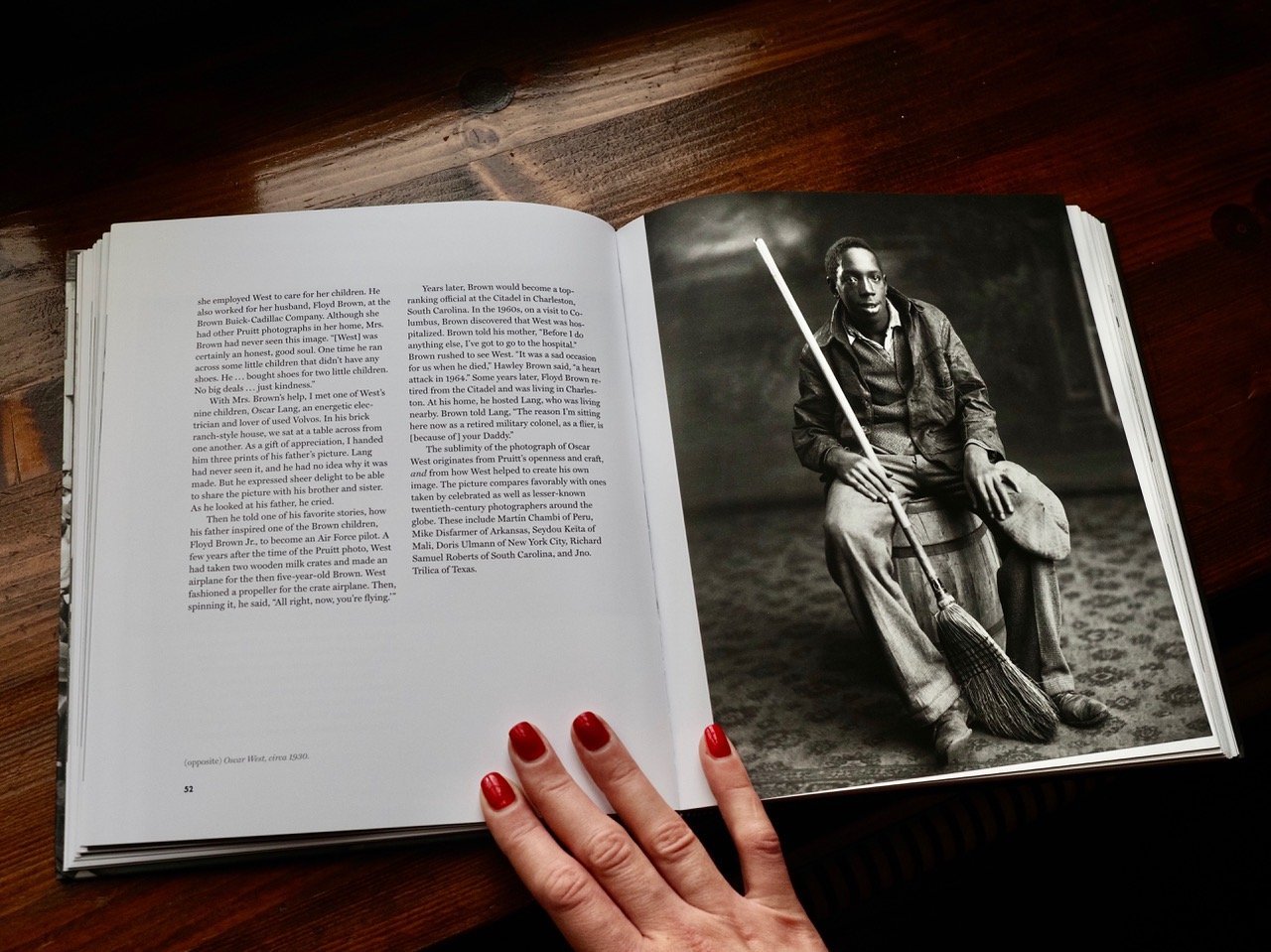

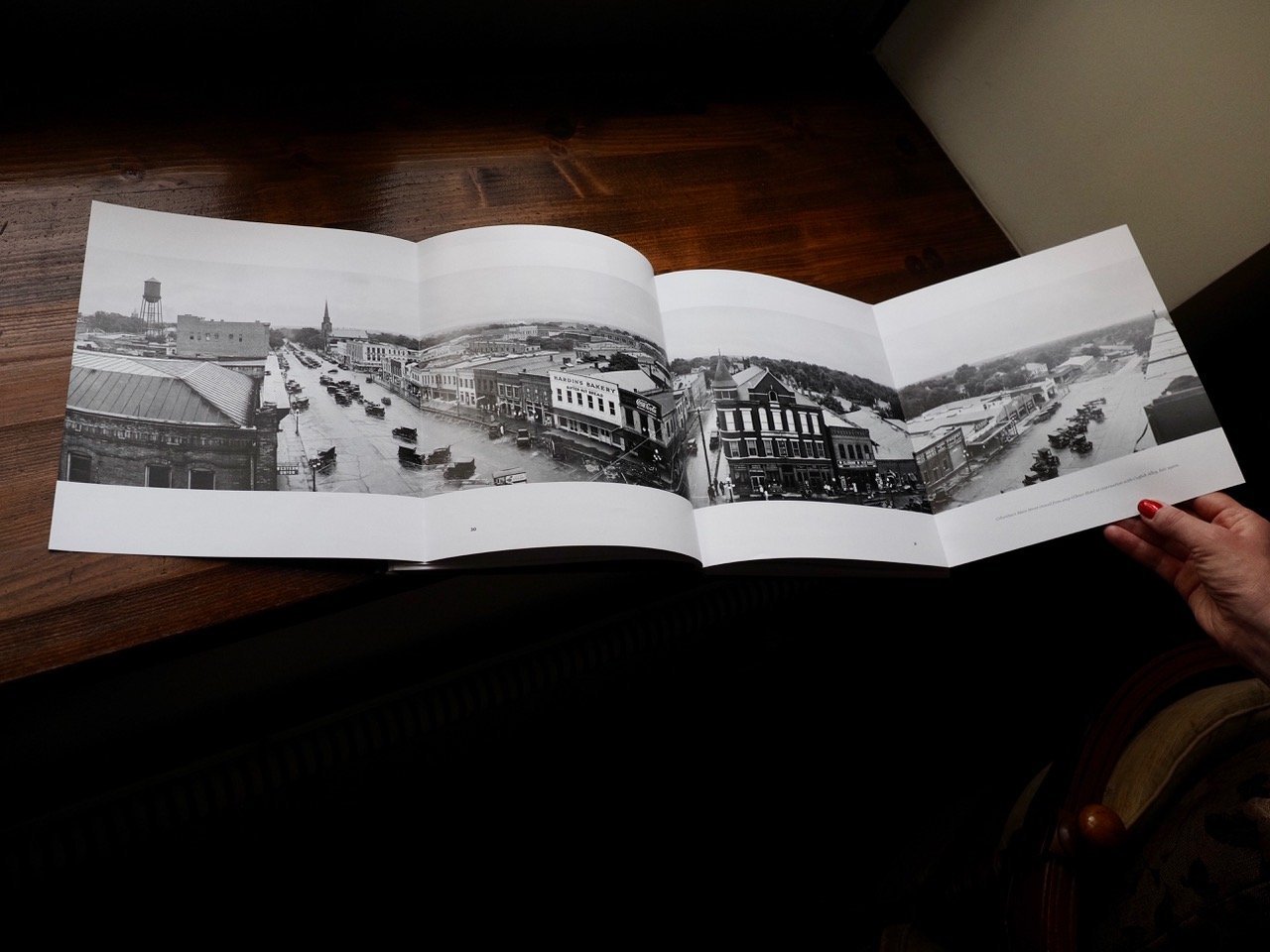

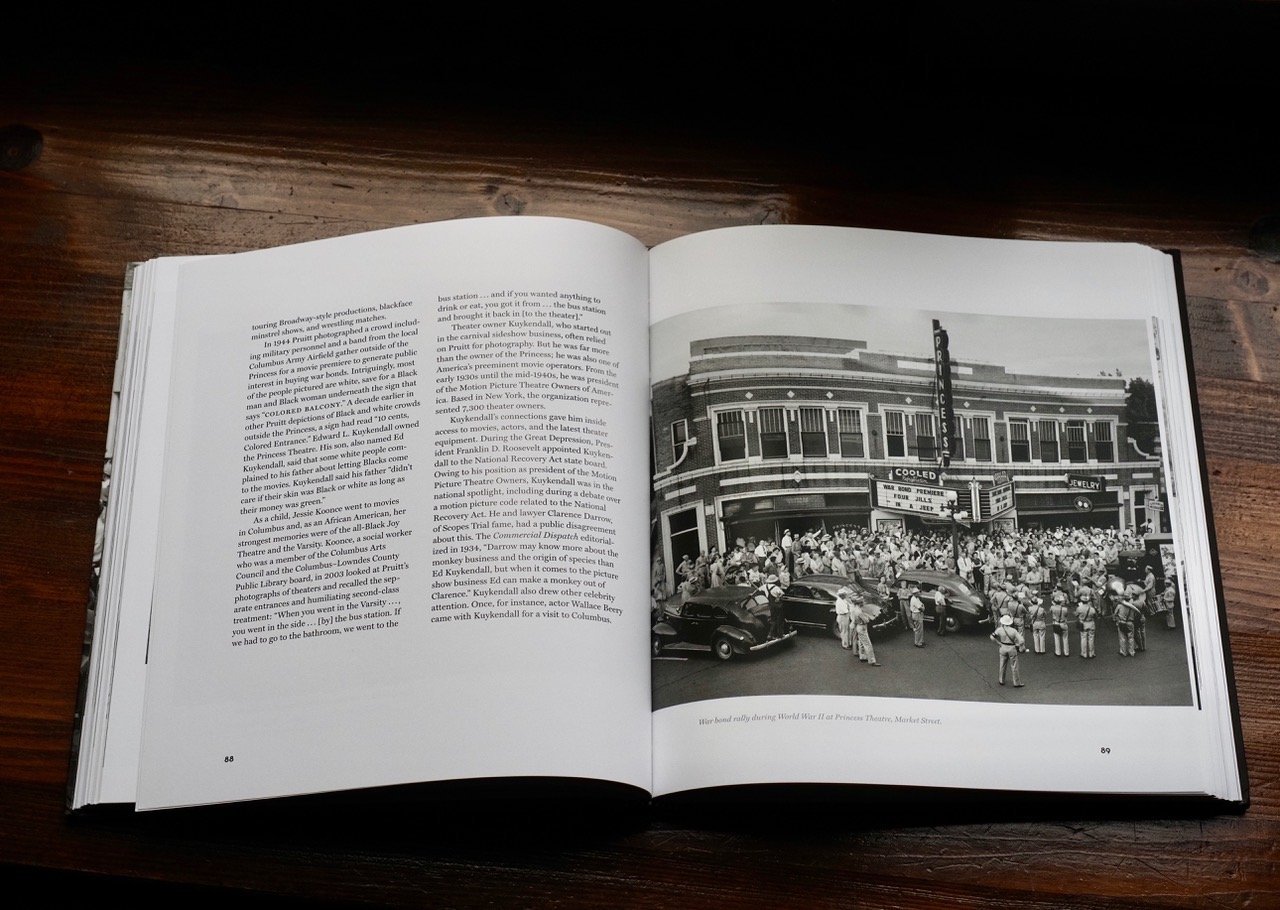

The photos themselves are not high art but are striking evidence of a wide range of people and events over a long time span. They are straightforward and workmanlike, mainly orders executed by local businessman Pruitt in his studio on Main Street or on assignment throughout the community and the county, as he worked for a diverse range of clients, both Black and white. Pruitt also apparently felt compelled to document some events even if there might not have been a specific client for the image. Hudson has chosen 194 photos from the 88,000—among them family and individual portraits, farmers, fishermen and hunters, circus performers, debutantes, sports teams, street scenes, grocery stores, barbershops, musicians, visiting celebrities, baptisms and church events, the deceased in their coffins, blackface performances, a condemned man and his executioners, and victims of a lynching. They were made variously on 8 x 10 sheet film, 5 x 7 and 8 x 10 glass negatives, 3 x 4 inch sheet film, 120 roll film, and in panorama format.

There is not much of a record of what Pruitt himself thought about his photographs. Hudson has left no stone unturned in trying to identify the people, locations and contexts pictured. He describes the painstaking detective work that went into identifying some of the subjects many years after the fact, including interviewing people pictured or their surviving relatives. Not all of the photos have captions, and some images remain enigmatic. The black boy with the bloodied nose next to a white boy of similar age: who or what provoked what kind of fight or assault? The young girl posing with a live rattlesnake—what significance did the snake have to the girl?

Hudson’s essays on the photos probe the ascertainable facts, and also meditate upon his hometown and some of the moral issues the images raise in light of evolving standards of justice. In explicating the images, Hudson weaves in excerpts from contemporaneous newspaper articles, quotations from Southern authors, and insights of well-known photography critics. It was obviously a road of self-discovery for him, telling him things about his hometown that he had not known, things which had been hidden from him by the social mores of his upbringing. Thus, he recounts that although he grew up in Columbus, he had not known about the Ku Klux Klan parade down Main Street in the 1920s nor about the 1935 lynching, both events depicted in Pruitt’s photographs and included in the book. The text frequently discusses how Pruitt documented both the Black and white communities, notwithstanding the artifices and cruelties of segregation. Since I overlapped (at least minimally) with the period documented, and am personally familiar with the Deep South, some of Hudson’s explanations of how racial segregation played out in everyday life seemed superfluous to me at first, but reflection suggests that not everyone knows those details, and the farther from that era we get, the more necessary such explanations may be.

This book will appeal to historians of both the American South and of photography itself, to students of race relations, and to libraries and educational establishments interested in Southern studies. It is difficult to imagine that taking possession of some longtime photographer’s external hard drives upon his retirement could be as exciting as the discovery of the Pruitt archives was to Hudson and his friends. But the impulse to preserve relics of the past is a human attribute even if a hard drive strikes us as less exotic (and perhaps even more ephemeral) than glass plates. The Pruitt collection was crying out to be saved, and we are fortunate that Hudson and his friends heard that cry, and persisted when it would have been easier to move on to other pursuits. This book might also inspire some people to look about them for a photographic record worthy of preservation. It might be in someone’s garage, in a dusty attic or dark basement (or even on a hard drive). Having seen this book, someone might regard the contents of the attic or basement differently. How many archives of other photographers have vanished because no Berkley Hudson and friends stepped up to save them, archives from which, perhaps, a few images at most were cherry-picked, and the rest discarded to be lost forever?

O.N. Pruitt’s Possum Town: Photographing Trouble and Resilience in the American South by Berkley Hudson

Format: Hardcover

Dimensions: 9 x 10 inches

Pages: 272 pages

Release Date: January 2022

ISBN: ISBN: 978-1-4696-6270-1

Publisher: University of North Carolina Press (in association with the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University)

Designed by Kim Bryant

Printed in Canada on 100# Garda Matte paper.

Available for purchase at Long Leaf Services!

Available for purchase at Long Leaf Services!

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Patrick Murphy is an American photographer living in Vilnius, Lithuania. His photobook Reserved Mr. Memory, published in Vilnius in 2019, contains 59 film and two digital photographs taken over a 50-year period in his native American South, plus text. His works have been exhibited in Russia, including at Moscow Photobiennale; at several venues in Lithuania; and in the U.S. His book was included in book shows at the International Photography Symposium in Nida (Lithuania) and the Foto Wien (Vienna) Festival, and at photo festivals in Kaunas (Lithuania) and Bialystok (Poland). He participated in Review Santa Fe (N.M.) in 2021. He is a member of the Reflektor Group.

Connect with Patrick Murphy on Instagram!

Shadow Gather’s photos unveil nightlife’s raw, electric energy as spaces of defiant authenticity. Her Meow Wolf exhibition elevates marginalized stories, embracing imperfections as vital truths. Each image is a protest against sanitization, celebrating unguarded moments of liberation.