Interview: Dan Herrera’s Photographic Science Fiction

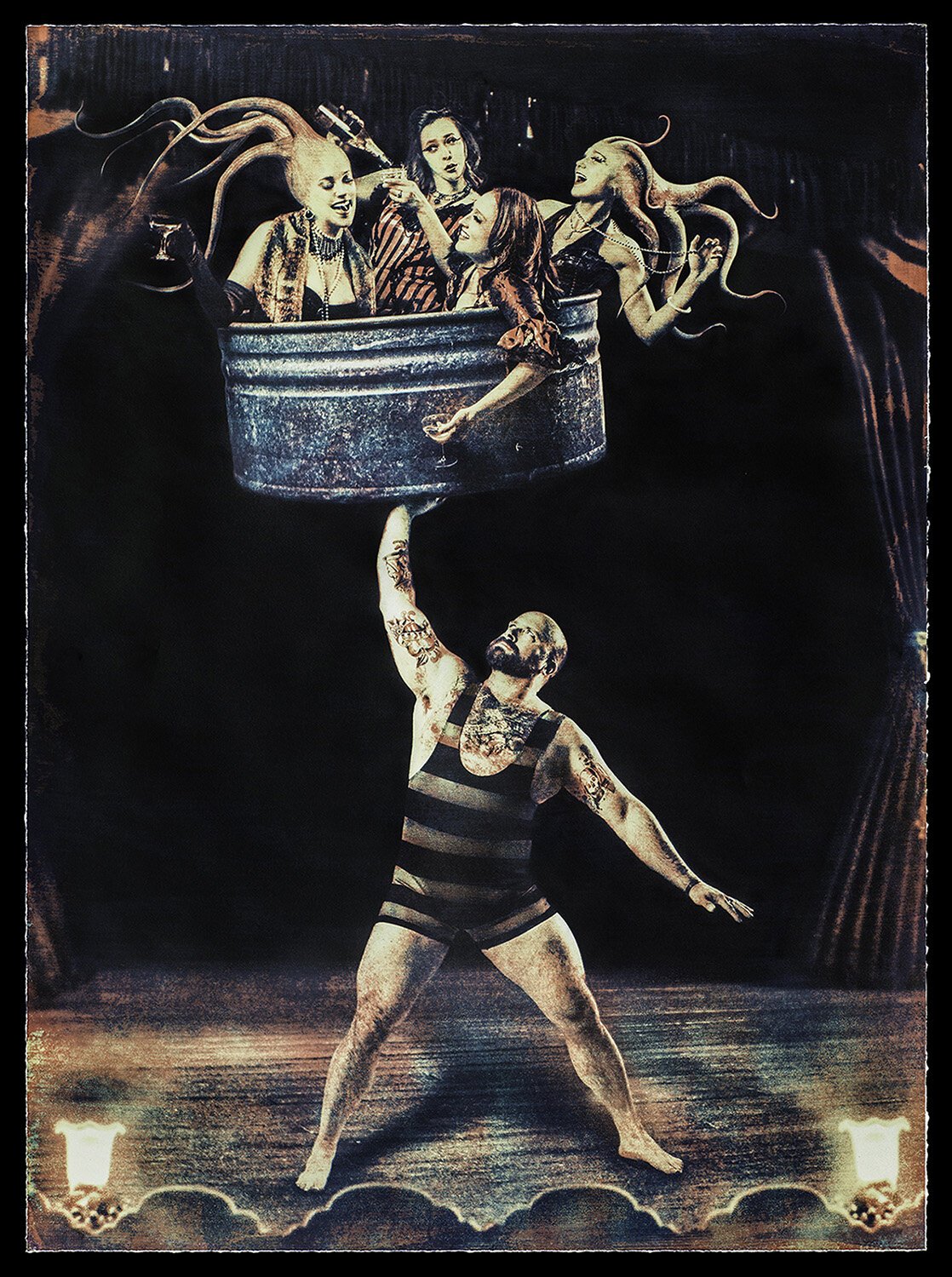

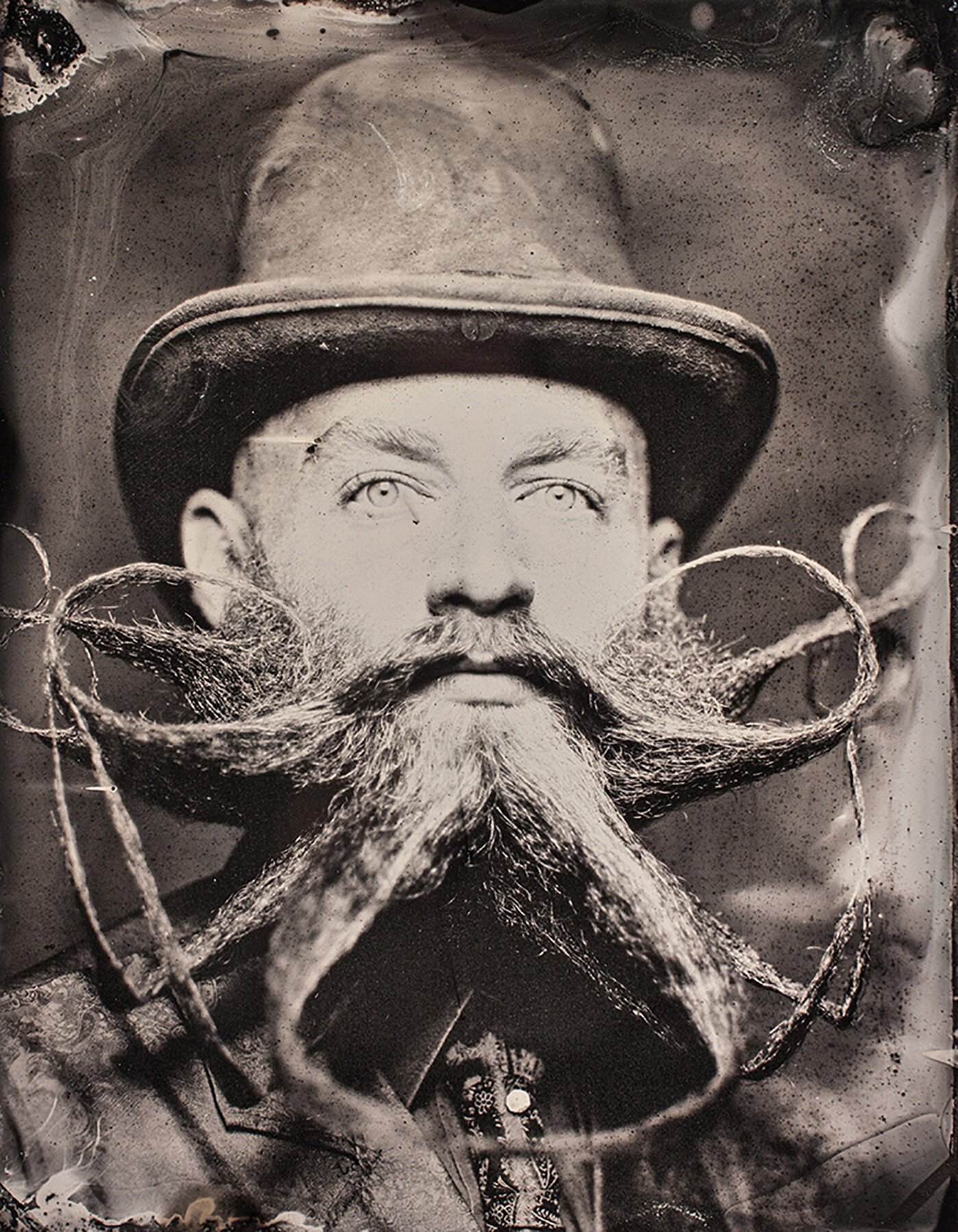

“The Wax Tickler” by Dan Herrera

How does one photograph science fiction? Can someone document an alternate past that never was? Dan Herrera is not just a photographer, he is a world builder, and the worlds he builds are filled with aliens and monsters, outsiders you find on the fringes. It's a bit HP Lovecraft, a bit Guillermo del Toro, a lot PT Barnum, all mixed up and re-imagined through a combination of modern and archaic technology.

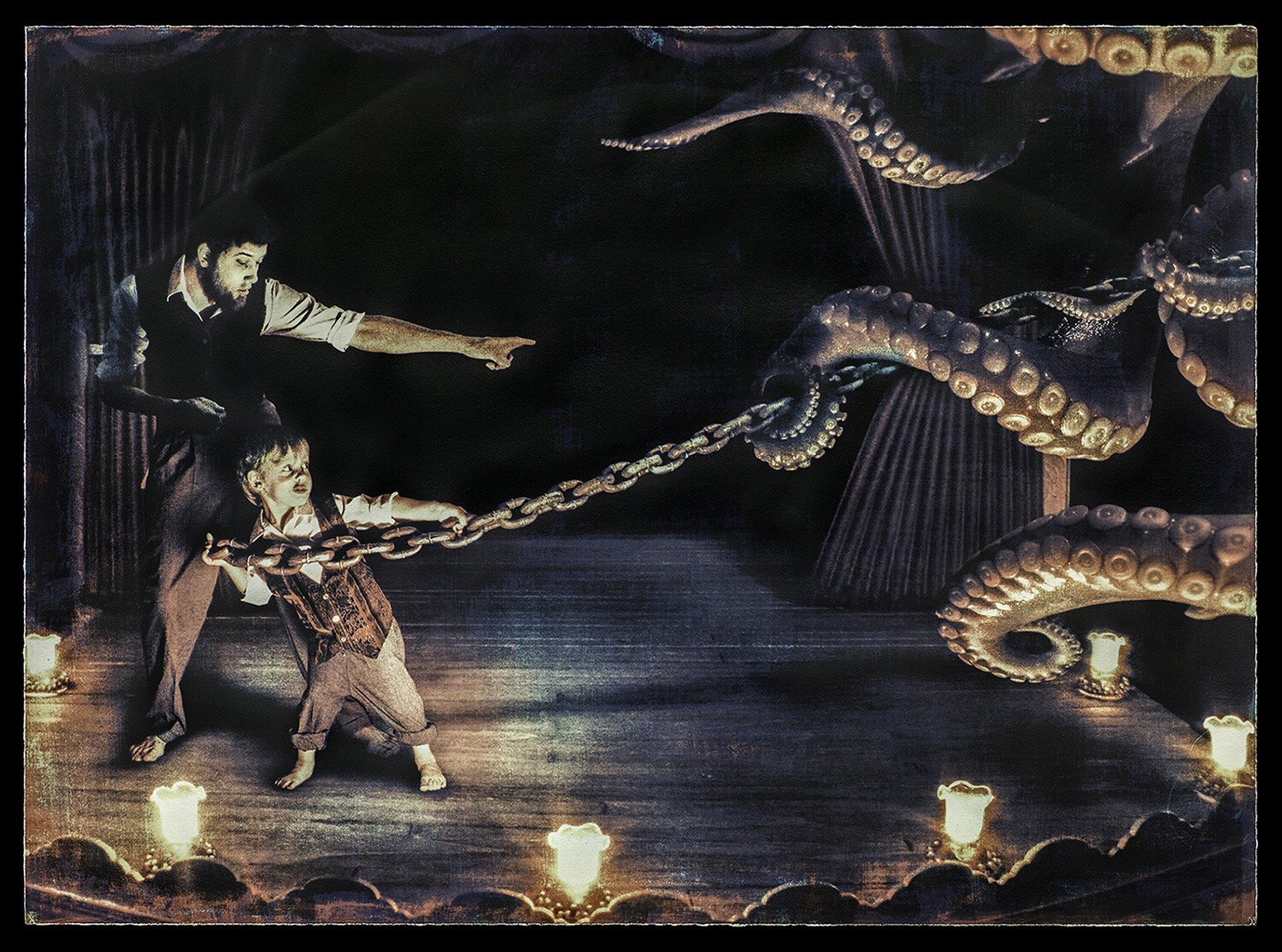

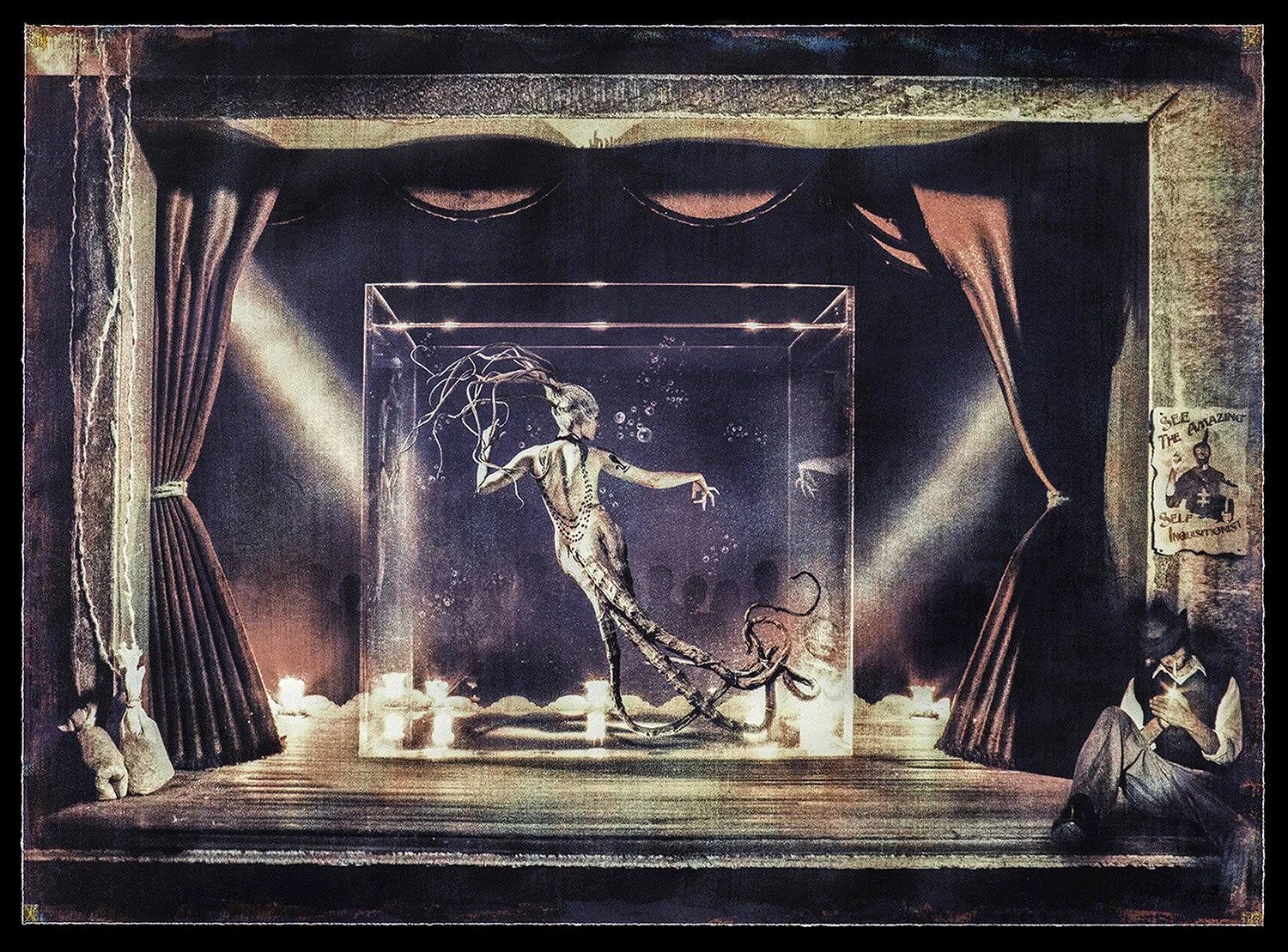

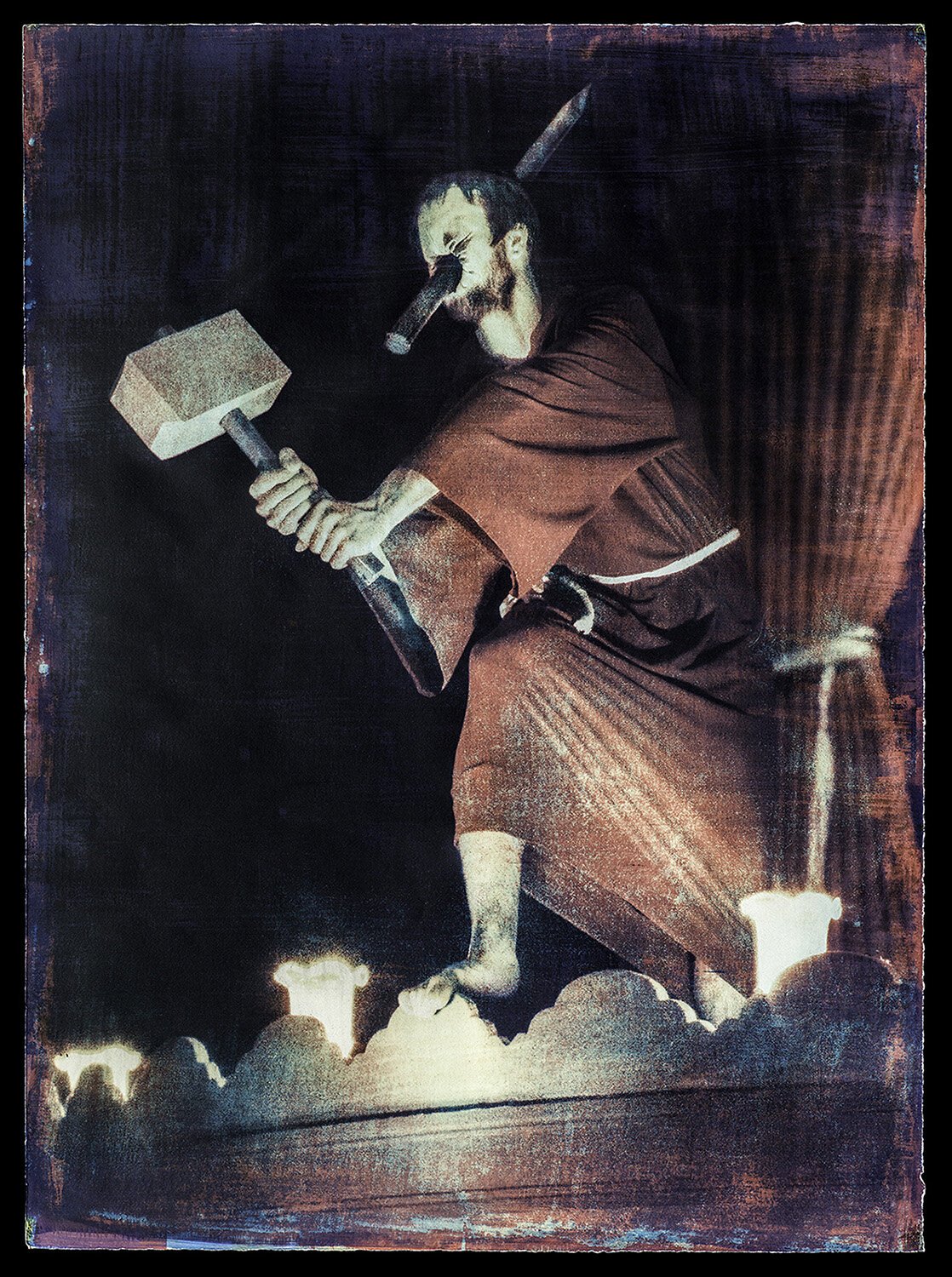

In his series Vaudeville, Herrara draws us into an imagined past where alien and human are thrown together in fantastical scenes within the spectacle of the sideshow. As carefully constructed as they are astonishingly imagined, each image in Vaudeville seems to tell a complete story which exists in this fully formed alternate universe. Rather than seeming dreamlike (or nightmarish), there is a viscerality to them that brings to mind Magical Realism, they are at once fantastical and familiar.

Almost as astounding as the imagery is the method in which they are presented, as large scale combination prints of cyanotype and gum bichromate. Working in these historical processes enhances the illusion that we are glimpsing into a past that never was. The full-color prints are just this side of garish, emphasizing the theatricality of the settings and the subjects.

You may be wondering if you're actually reading this on Analog Forever, because don't these look like Photoshop? And, yes, you'd be right, at least partially. I firmly believe in using the correct tools for the job at hand and decry any slavish ideology that says digital and analog shouldn't mix. While the imagery is digitally composited with models and props placed in miniature sets, the end result is completed in a hands-on 19th-century process. For those who are unfamiliar, the process of creating these prints is painstaking and time-consuming: each print is created through five individual exposures printed in precise registration over the course of four days. Gum bichromate is a finicky and maddening process but allows the artist a freedom of expression through color, texture, and brush strokes, all resulting in a unique print that has a depth of character that cannot be replicated.

I spoke to Dan Herrea from his home in Sacramento, California, the place where he grew up and is now settled with his wife and their four-year-old son. In addition to the Vaudeville series, we discussed his newest adventures in the wet plate collodion process. After you are done reading our interview make sure to connect with Dan on his Website and on Instagram and watch his video “The Wax Tickler” process video on YouTube!

Interview

“Encounter at the Well” by Dan Herrera

Niniane Kelley: Who are you? What's your deal?

Dan Herrera: My name's Dan and I've been taking photographs for pretty much as long as I can remember. I first started taking photographs when I was around 8, I used one of those crappy plastic 110 cameras and rode my bike to Thrifty grocery store to drop off the film. A lot of people have the same sort of story about falling in love with photos. And a lot of what I do now isn't really that different from what I did as a kid, things like making forced perspective photographs or taking photos of my action figures having epic battles.

NK: When did you start seriously studying photography?

DH: I first took a class in high school and that took my hobby to another place. Instead of shooting on crappy color film I could develop my own black and white film, which I thought was rad. All of us remember our first time in the darkroom, you get to see the image come up out of thin air, essentially. I originally wanted to be a marine biologist but the math involved in the science classes turned me off. But I took a Photoshop elective and I thought that was mindblowingly cool. I was doing simple manipulation in the darkroom and then I realized that if you can get it into the computer it opens up a whole new world. So I think that was the point where I realized I wanted to study photography.

NK: That must've been fairly early on in the evolution of Photoshop.

DH: It was version 2.5 or something, it was way early on. I think the magic wand tool had just been invented and layers was still pretty new. When I tell my students that I've been using Photoshop since 1998...some of them aren't even that old, which is pretty trippy!

NK: You then entered the BFA program at San Jose State and, like myself, the direction of your work was strongly influenced by Brian Taylor's alt-process class. You go from being immersed in digital to utilizing these 19th century handmade processes.

DH: Their darkroom program was one of the best in the state at the time and they had some of the largest facilities. Brian's the one who took me under his wing and showed me all these cool processes. At the time I was hardcore into Photoshop, it seemed like the way of the future, and he was like, what if we looked back, even further than the black and white stuff I had done before. And that really blew my mind, working with all these incredible potions, it added a different level of appreciation for the craft of photography.

There's a distinct line I draw when I look at the work I've done pre-alt-process and post, the imagery is similar, but it takes on a new life. I take that perfection (of the digital image) and then throw it through this wonky process that dates back almost 200 years. It breaks it up and reassembles it into something that's better than it was to begin with, there's something that I really find satisfying about that. There's a rich robustness to that actual physical object and it doesn't necessarily translate once you re-digitize it to show it off on Instagram. There's something very special about the actual thing and looking at it in person.

And I think that's especially important now because most of what we experience is through our phones, the idea of the handmade thing is becoming more and more precious and rare. The average person, how many photos do they actually print? This is one of the reasons I really like working with gum printing because each one is super, super unique, and also now with the wetplate because you only get one. There's something totally romantic about how the light actually touches the plate that the person gets, it's the original thing.

NK: Where do you get your inspiration from?

DH: Where does anyone's inspiration come from? The search for Inspirado... There's a lot of pop culture references that I steal and reassemble, but a lot of it is just thinking about things and writing them down and making a quick little sketch. I get a lot of inspiration now from my kid, as cheesy as that sounds. A lot of what I do is reflective of a childlike wonder and spirit so actually having a child now is pretty great because we can fantasize and talk about cool monsters and things like that. He's really into monsters right now which is fun because I can have someone to talk about it with besides my wife, she's tired of it.

“The Uncertainty Principle” by Dan Herrera

“The Shrouded Mire” by Dan Herrera

NK: With the Vaudeville series you've constructed an entire fantastic universe that the work inhabits. Where did that come from?

DH: I was reading a bunch of Iain M Banks books and a lot of HP Lovecraft so it started with this idea of a futuristic past. I started to think about timeline stories and how our history would look if there was alien contact and I placed that idea into the context of the turn of the 20th century. Then I thought about what photo processes were being used, and gum bichromate was really popular around that time and it matched the look I wanted. I was writing a lot of short stories and stream of consciousness so there's actually a wealth of information that I don't quite know what to do with. At one point I thought of publishing a book of the images with some of the writing.

NK: With Vaudeville there is digital compositing going on, but there's also a lot of set building and real-world effects that go into making the image.

DH: I work with a lot of costume artists and practical effects makeup artists. So some of what I do is Photoshop manipulation, but a lot of it is just making sure the lighting is right and dressing people in costume and having prosthetics applied before the photoshoot. I also make small sets and little dioramas and props specifically to photograph from a certain angle, so that's what part of it is, too.

“Gunslinger” by Dan Herrera

NK: One thing with the Vaudeville prints that is lost online is the scale of them. They're actually quite large, particularly for gum prints, so as a viewer they're impressively in-your-face, they're quite impactful with the combination of the size and the color and the imagery.

DH: The idea of looking at something small is special. If it's small the person has to get up close and it's this intimate, quiet moment between the two. But with these, with the backstory and the imagery itself, I wanted to be a bit louder and project a bit more. I wanted the image to be more grandiose and menacing, but I was also pushing myself to see how big I could make a really tight print. As you start to scale up things can go wrong, it's more complicated. And there's something that happens at that size that gets confusing for the viewer – is this a photo, is this a painting? And since there's this fantastic imagery to begin with there's a lot of suspension of disbelief I want to happen for as long as possible and I think the gum process helps with that.

NK: Where do you find the models you use for your work?

DH: Originally, like most of us, I initially used friends and family, but as I started self-promoting I would have people reach out to me and if they had a certain look I would recruit them. That turned into a small network of eclectic looking people who wanted to work with me, which is just fantastic. And with the portrait stuff I'm doing now, it started with a Halloween shoot where I was doing super colorful, pop-y portraits of the guests and somebody from a local beard and mustache competition club saw those and reached out to me. That was when I was first starting to get into wetplate and I was researching the history of portraiture and was thinking it would be really cool to photograph cosplayers, professional beardsmen, and other fun eclectic looking people using the wetplate process.

NK: In all your work there's a grand theatricality to what you do, where does that come from?

DH: There's something fascinating about the spectacle of stuff, it's one of the reasons we like guilty-pleasure reality tv or watching a car crash. I don't necessarily always consciously try to inject that into my work but I enjoy that kind of stuff so much it just seems like it finds its way in. And the idea of pictorialism and the romanticized ideal lends itself to theater in a lot of ways. It's something I'm really drawn to so that finds its way into what I do, as well.

NK: What's next for you? Any new projects that you're working on?

DH: For me it's always a slow boil. I keep a journal with all my ideas, so I'm never short on things that I could do it's just a matter of whittling down the ones I have time for, because time is so precious. But I also do a lot of tintype portrait bookings too, which is cool because it's a weird hybrid gig where I'm indulging my need to do this alt-process stuff but I'm also getting paid to do it for people. I'm also photographing the beard and mustache competition again in March. But with my personal projects I'll be chipping away at four or five projects at once, so it seems like nothing's happening but then all of a sudden they'll come to fruition.

Gallery

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Niniane Kelley is a fine art photographer living and working in San Francisco and Lake County, California. A native of the Bay Area, she is a San Jose State University graduate, earning a BFA in Photography in 2008. She teaches workshops in the Bay Area and surrounding environs. She most recently worked as a photographer and manager at San Francisco’s tintype portrait studio, Photobooth. Connect with Niniane Kelley on her Website and on Instagram!

These images are the AF Team's curation of the most stand-out must-see images produced in 2024. From career photographers to amateur hobbyists, these scenes and portraits made a huge impact this year!